AI as politic of class exploitation

Published:

In the grand debate about AI and its implication for society, a particularly important concern that justifiably receives a lot of attention is the likely impact of AI on workers. A lot has been written about this in recent years informed by ongoing critical work in this space. However, mainstream public discourse often reduces that conversation to “AI automation will kill jobs”. That framing while not incorrect, is too reductive and fails to capture the systemic crisis that may be in front of us. It also has the insidious effect of bolstering a technodeterministic view that imagines a fabled race between “humans vs. machines” at the heart of the issue, with Big Tech and Silicon Valley simply acting out in roles preordained to them rather than being active participants in subverting technological progress towards unprecedented wealth and power accumulation. That framing claims with self-righteous indignation that it should be self-evident that technological progress will increasingly make bigger strides and therefore the machine is inevitably destined to surpass human capabilities at some point, and it is society that must constantly evolve to survive the new realities. What is left to debate then? If you do not agree it must be because YOU are a technophobe, a luddite, anti-progress, and anti-AI. I will reserve my temptation to rage against the tech-bro arrogance that dehumanizes us all by reducing us to “collections of skills of economic value to the capitalist system” for another time. But I do think we should talk about why this view is not just dangerously wrong, but nefarious at its core. It is a deliberate erasure of critical thought and scholarship on this topic to conceal the true reality of mass dispossession of workers, undoing of decades of labor right progress, and a drumming up of neocolonial extractive practices and class exploitation that is unfolding in front of our eyes.

So, buckle up! We are going to talk about how AI is saliently a politic of class exploitation.

The bigger picture

To understand the implications of AI for the working class, we must not just consider the direct risks from the technology itself but redirect our gaze to the several systemic consequences of what the technology does, how it is made, who it is intended to serve, and the broader sociopolitical context in which it is embedded. I am drawing from a co-authored paper we published last year at the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT) where we took a similar perspective but in the more constrained scope of AI-mediated enterprise knowledge access. In the rest of this post, I will briefly talk from my personal perspective about some of the ways in which AI commodifies and appropriates labor and marginalizes the working class. These consequences, among others, co-constitute the conditions under which we are starting to observe a systemic dispossession of working-class status, power, and wealth.

AI commodifies labor

If you are a screenwriter or a visual artist, your work bears a distinct mark of your personal style and identity. It speaks through your voice, sees the world from your perspective. It is that distinctiveness that makes it challenging for others to treat you as interchangeable with other artists, i.e., prevents your labor from being commodified. Commodification of labor refers to the acts of transforming labor into commodities, defined as objects of economic value whose instances are treated as equivalent, or nearly so, with no regard to who produced them. When your work is distinct, you have negotiation power because no one else can produce the same as you. Commodifying labor is the eternal capitalist project, from the factory floors to now our studios and writers’ rooms. By commodifying labor, capitalists can renegotiate compensation for labor and drastically bring down the cost of production by pitting worker against worker.

Most technological automation transforms the fundamental nature of the underlying task and commodifies the labor required for the task in the process. But there is something distinctive about how salient commodification is to the design of generative AI applications as tools for writing, generating visual arts and music, producing code, and assisting in other knowledge work.

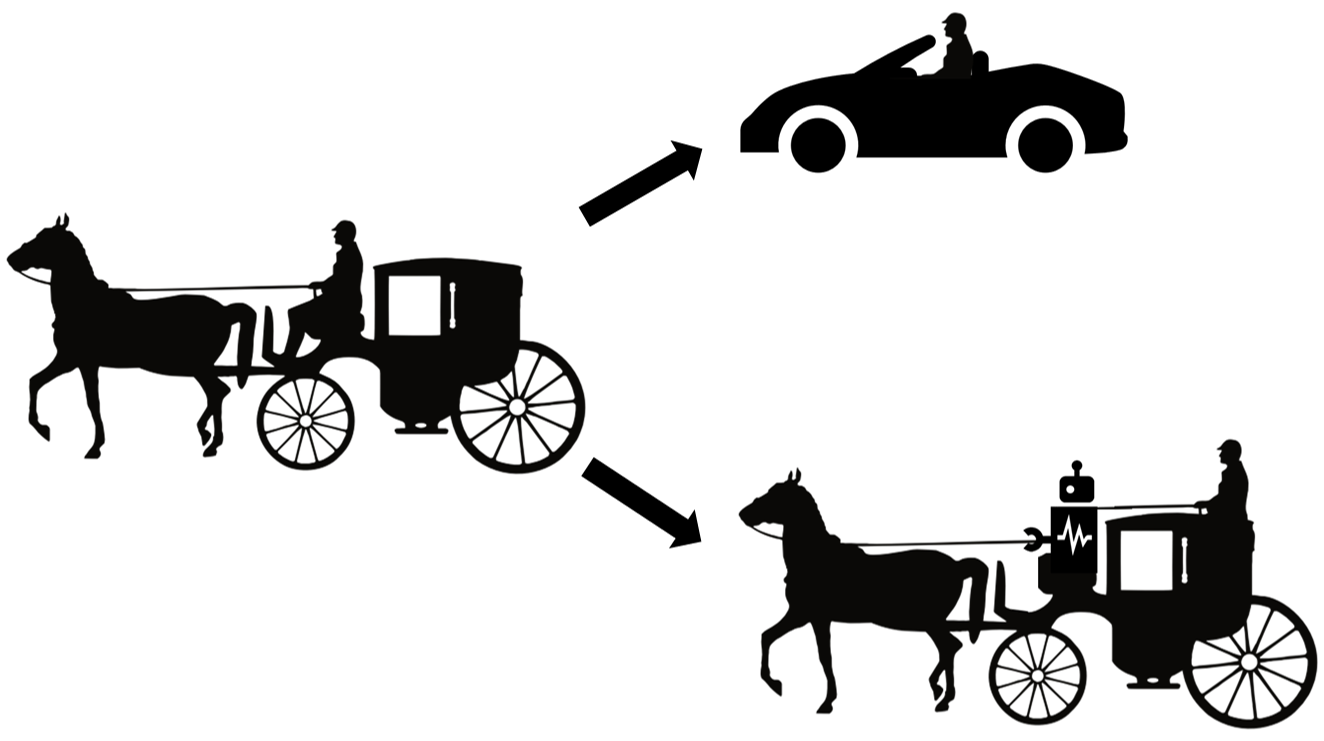

What are we automating? When you think about automation, you might imagine a group of inventors looking closely at a labor-intensive task and ideating how the problem can be approached differently to cut down the time and labor necessary to complete the task as well as to enable performing the task more effectively than hitherto has been possible. As a caricature of an example, if you have a horse carriage, you want to invent the automobile to both reduce how hard the driver must work while also improving the distances they can travel and the speed of transport. Now, imagine in an alternative universe a group of inventors got together and instead of focusing on the horse and the carriage, redirected their focus entirely on what the driver was doing and built an approximate model of the driver. The model itself is unintelligent and simply tries to predict at each moment what would the driver do, and invariably it often gets it wrong. So, now the job of the driver is no longer to drive the vehicle but to constantly monitor and correct for the model’s mistakes. Instead of discovering the joys of driving an automobile and travelling longer distances more comfortably, the driver now sits atop the same slow horse-drawn carriage constantly supervising the model. This would make for a rather hilarious cyber-punk fiction if not for the fact that it is a rather apt metaphor for what we have come to call as “AI” today.

Are you automating the carriage or the driver?

Think of generative AI models that generate documents, code, images, and videos in response to prompts. In all these cases, the model is fundamentally trained to mimic what a human would do. Inserting this model in between the task and the person responsible for the task changes the very nature of their responsibilities. They are no longer screenwriters, visual artists, musicians, or coders. They are now prompt engineers tinkering with the words with which they express their requirements to the algorithm and then spend more time trying to massage the outputs. To many artists and knowledge workers this represents an end to their craft, the replacement of creativity with mindless (re)production, a loss of a deeply personal source of pride and joy, and a justifiable fear of the drudgery of continually turning knobs of the machine till it accidentally produces something passable. For some, experimenting with these tools are indeed joyful in their own ways, and some will find creative ways to use these tools to expand the boundaries of creativity. But what this technology can do for some coexists with the concerns of what it will do for most shaped by the powerful forces of capitalism.

For most, this commodification not only distances them from the crafts they enjoy and moves them to a functional role of lower status but also translates to a significant loss of compensation because their new function is viewed as requiring less-skills that can be performed by any of the surplus of workers available in the market. The surplus from any actual productivity improvements, if any, from the usage of these tools will be collected exclusively by the capitalist class. On the other hand, artists and knowledge workers will be expected to produce more to deserve the same compensation. Many of these roles will also become susceptible to gigification which will further correspond to many in the working-class losing benefits and protections associated with full time work that decades of labor movements have fought to put in place.

Note that this loss of compensation is tied to the perceived simplification of the task and corresponding speculations of productivity boosts. If producing an article using generative AI and then editing it takes similar effort as writing it without these tools, that is of less consequence in the compensation negotiations than the speculated productivity boosts that the dominant AI narratives may have convinced us to buy into. It is exactly for this reason that the “AI hype” is not extraneous to the value proposition of AI, but rather is an integral part of the same package. The key profit-maker here is not the productivity tools, but the social construction of the AI productivity myth that creates the exact conditions that the capitalist class so eagerly desires to renegotiate down the compensation for labor.

And when something goes wrong or when the outputs fall far below what is desired, the blame will not be attributed to the mindless algorithms, nor will it land on the shoulders of the bosses who force their employees to use these technologies. It is the workers who will be ultimately held responsible for quality control who will now also serve as the systems’ moral crumple zones.

AI appropriates labor

The risks to the working class from AI are not limited to their impact on labor when these technologies are put into use. Many of the concrete harms are direct results of the appropriation of data labor necessary for the development of these systems. If you are unfamiliar with the invisible human labor force that powers so much of our AI technologies today, I recommend starting with Gray and Suri’s “Ghost Work”.

Grand theft data labor Data labor is defined as “activities that produce digital records useful for capital generation”. Appropriation of data labor includes underpaid crowd work for data labeling and content moderation that are critical for training and operationalizing AI models. It also includes the uncompensated appropriation of works by writer, artists, and programmers created outside of the AI development process that are nonetheless extracted from the Web and fed in as training data to generative AI models. It furthermore includes the user behavior data and other data generated when users interact with and participate on the platforms, i.e., simply by using these systems, they generate more data for the AI model to train on to further automate exactly the type of tasks they are currently performing.

It is particularly harmful that these AI technologies developed on appropriated labor is then employed to displace and automate the jobs of those whose labor was appropriated, e.g., artists, coders, and other knowledge workers. This may result in vicious cycles of skill transfer from people to AI models whereby proprietary AI model capabilities continue to improve—by learning from both what the workers produce and from the traces of their personal workflows captured by the AI platforms when workers interact with them—while workers progressively lose their economic value and power.

AI for me, data labor for thee Another pernicious aspect of AI data labor dynamics is how they mirror and reify racial capitalism and coloniality, employ global labor exploitation and extractive practices, and reinforce the global north and south divide. While worldwide jobs might be created in certain cases, the workers are typically low paid and deprived of any share of the profit made from technologies built with their labor. These dynamics encompass accruing the benefits of generative AI to privileged populations in western and other rich countries, while data labor is relegated to already marginalized populations, for example, in the global south. Communities that significantly contribute to AI data labor may even find their own linguistic styles being labeled AI-ese and being forced to repeatedly prove their own humanity.

The ghost in the machine is us When AI models are trained on writings and other works of people, it is not merely appropriating their labor but also their identities. Imagine a film, a video game, or a video ad that includes an AI-generated character who is Black. The character was created based on limited instructions in the prompt with the AI model filling in all the remaining details. No Black person was hired to play that character nor to write it. The AI model is simply drawing from the ghostly echoes of all the stories and lived experiences of real Black people in its training data. The model nor the person using it to create the character could ever experience the joys or the struggles of being Black, nor can they truly appreciate the history and culture of its peoples. The character wears that identity as a hollow shell, reconstructed from an amalgamation of the entirety of human experience as it is shallowly reflected on the web, and has its strings pulled to say or act in ways that a real Black person might strongly oppose to. This is the new “Digital Blackface”. This is the great displacement of art that tells the stories of its peoples by synthetic content.

AI marginalizes the working class

Let them eat chatbots The adverse effects of AI on the working class are not restricted to the commodification and appropriation of labor. AI technologies are also being positioned to provide cover for depriving the working class from basic services such as healthcare and education. Most of us I imagine have heard at least one AI-bro predict that the solution to the scarcity of doctors, teachers, and therapists in under-funded communities is to give them access to AI chatbots designed to serve in those functions. This idea is not just particularly ill-premised, it is maliciously ableist, classist, and racist, and mirrors the already ongoing dismantling of social services globally. Our communities globally are suffering from lack of investments in those communities because of generations of class, colonial, and racial oppression. A capitalist society only invests in communities to the extent that it in return supports more capital accumulation for them. It wants us to forget that healthcare and wellbeing are universal rights, not privileges. It wants to forget that education is supposed to liberate us and teach us to find community in each other, not to be perfectly shaped into cogs for the capitalist machine. So, of course instead of meaningful investments in our communities to affect social change it wants us to further divert investments towards Big Tech. Chatbots in this context aren’t meant to be real solutions, just a placebo for the masses, and a cover for further dismantling of our social infrastructure. Put Big Tech in charge of education and it almost surely also guarantees further dismantling of Humanities and every other critical pedagogy that is supposed to teach us to resist capitalism, colonization, and oppression.

Note: There are incredibly exciting work happening in the AI-for-science space. That is not what I am referring to here. The research in AI-for-science is categorically different from research in generative AI technologies like LLMs, in terms of the orders of magnitude less resource requirements for model training and in having much clearer paths towards real societal impact. That is not to say they also do not raise some societal concerns, e.g., for creating the conditions for more health data extraction from parents that tech companies can then monopolize. But overall, I personally believe it is important that we separate that class of problem-specific machine learning technologies from the LLMs and other generative AIs of the day in these conversations.

The environmental costs of AI The environmental impacts of global data center expansion for AI are also being felt disproportionately by already marginalized and vulnerable communities. Climate change is a racial justice issue. Climate change is a social justice issue. Instead of investing in our social infrastructure, protecting the already vulnerable communities, and taking drastic steps to reduce our fossil fuel emissions, Big Tech wants you to believe that AI will solve climate change. Of course, it won’t. And coincidentally all of Big Tech’s climate pledges are also a hot mess (pun intended). It is remarkable to me that of all things it is chatbots that the ruling class has decided is worth burning the whole planet down for. This is naked necropolitics.

To summarize, generative AI technologies developed using theft and appropriation of data labor are commodifying the jobs of those whose labor it appropriates, and then acting to provide political cover for the dismantling of social services while also dangerously accelerating anthropogenic climate change that disproportionately impacts vulnerable and marginalized working-class people.

Resisting our AI capitalist overlords

Imagining new futures, learning from our past It doesn’t have to be this way. Technology is not inherently repressive. But it does have its politics. Technology is shaped by our visions of desired futures, and in turn actualizes social transformations towards envisioned futures. And that is why the AI hype is dangerous because it manufactures a crisis of imagination, trying to convince everyone that the path we are on is the only possible future, and aggressively rebukes anyone for questioning or resisting their desired future being forced on all of us.

"The exercise of imagination is dangerous to those who profit from the way things are because it has the power to show that the way things are is not permanent, not universal, not necessary."– Ursula K. Le Guin

So, let us critically ask, whose sociotechnical imaginaries are we granting normative status and what myriads of radically alternative futures are we overlooking? How does increasing dominance of Big Tech over academic research and policy constrain the kinds of technologies we are allowed to imagine and build? What would AI and other technologies look like if we designed them for futures informed by feminist, queer, decolonial, anti-racist, anti-casteist, anti-ableist, and abolitionist thoughts, and if the focus of our work was not to prop up colonial cisheteropatriarchal capitalist structures but to dismantle them? As Ruha Benjamin argues, exercising our imagination is “an invitation to rid our mental and social structures from the tyranny of dominant imaginaries”. So, how do we go about liberating ourselves from the dominant neocolonial capitalist imaginaries of AI, and radically reimagine what technology could be and redefine our desired relationships with technology?

There has been growing interest on this topic in recent years. There was a CRAFT workshop at ACM FAccT’24 conference titled “Better Utopias: resisting Silicon Valley ideology and decolonizing our imaginaries of the future”. DAIR organized a workshop earlier this year on “Imagining Possible Futures”. I have been thinking about this topic myself and wrote a paper in the context of information retrieval research.

But this is not a call for idle speculation, this must be an integral part of our day-to-day emancipatory praxis. For example, if you work on developing AI tools and systems for knowledge work, ask yourself who you are building it for, the workers or the bosses? How would your approach and design fundamentally change if your goal was explicitly to shift power from bosses to workers? What mechanisms of collective action and resistance would you build in into the system design? What technologies would you develop to empower artists and knowledge workers to safeguard the artefacts they produce from being commodified and appropriated (example)? What direct actions can you take today to challenge the AI hype and its uncritical adoption within the tech community? What spaces can you create for collective learning about the history of labor movements, for collective sensemaking of our current challenges and risks, and for collective organizing (unions and otherwise)? We must remember that it is not just our desired futures that should inform our actions in this present moment, but also our past. Learn about the true history of the Luddite uprising, and ask yourself what would be the equivalent of “machine breaking” for our generation?

Workers of the world, unite! This is the moment for movement building. It is incredibly difficult work, as it always has been throughout history. It requires us to reconcile collective risks and systemic harms with individual circumstances. I am empathetic towards those who may genuinely find these tools useful. I am aware of some of the ongoing debates around AI art and accessibility, and again I empathize with those arguments. I don’t believe these positions are irreconcilable, but it does require bringing a multitude of people to the table to build solidarity, find workable solutions, collectively strategize, and build a movement. Because we cannot let Big Tech co-opt our differences to divide and defeat us. We should resist when Big Tech tries to pry open those cracks and claim that AI shaming is “ableist” or that it arises from “class anxiety induced in middle class knowledge workers” and intended to protect “privileged class of knowledge work”. Nuh uh! Our liberation is bound together and capitulating to the politics of AI hype will be catastrophic for the entirety of the working class. And we must also outright oppose when Big Tech claims that the path forward is to “upskill artists and knowledge workers to leverage AI” because training artists and knowledge workers to prompt an AI model is not teaching them a meaningful new skill but luring them to abdicate their craft, creativity, and critical thinking.

So, workers of the world, unite! We have nothing to lose but our cha… chatbots.

Would you like to comment on or discuss this post? You can do so on these social media threads on Bluesky, Mastodon, LinkedIn, and Twitter.